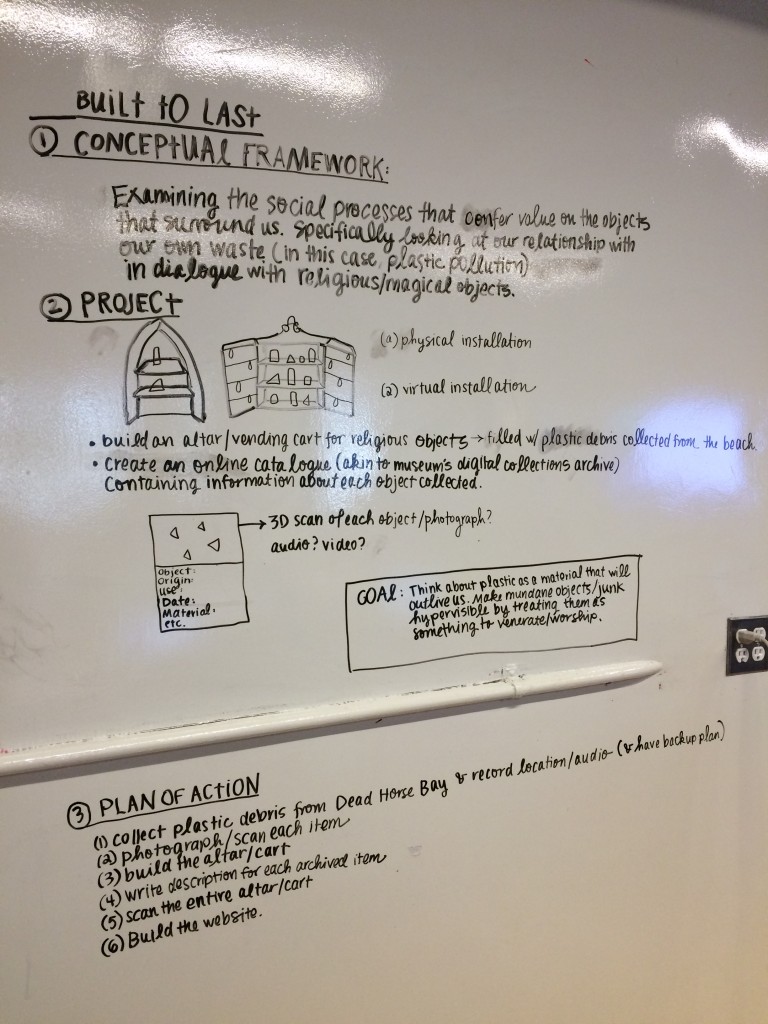

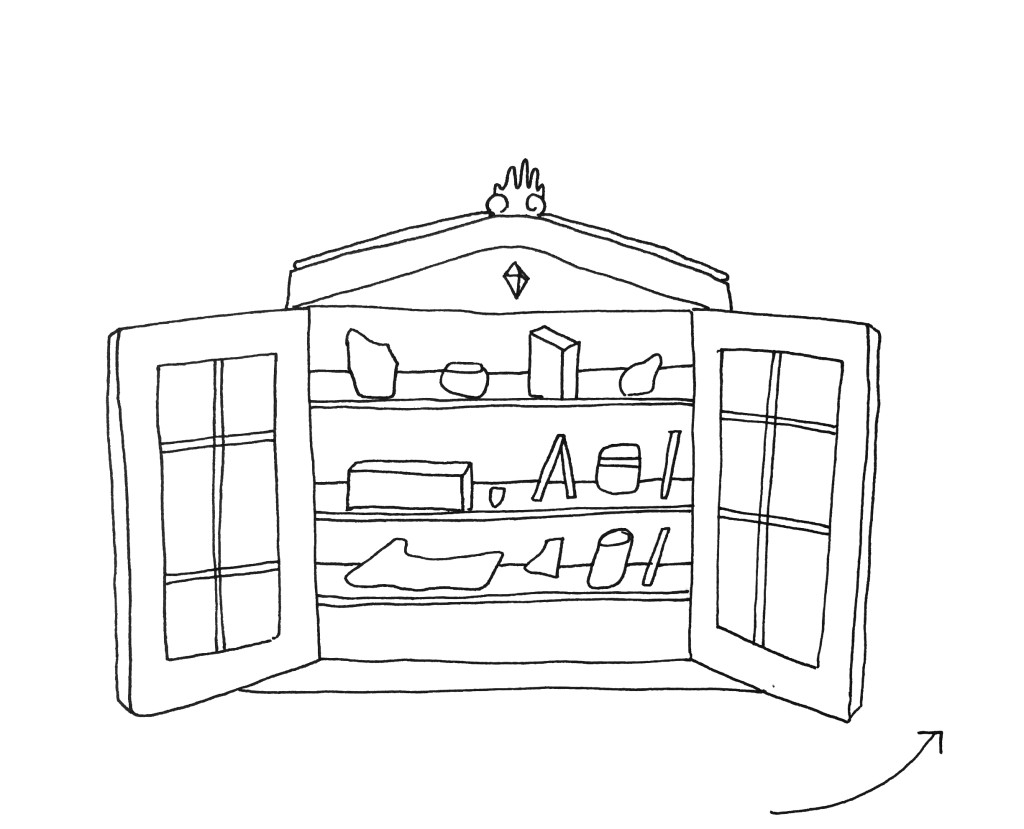

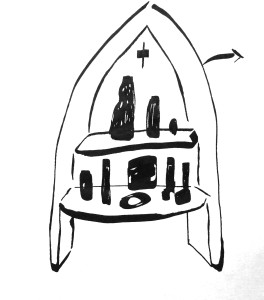

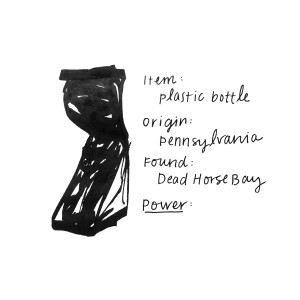

plastic in paradisum is a digital, interactive archive of plastic objects I found washed up on the beach at Dead Horse Bay. It’s a creative interrogation of the social processes that confer value on the objects that surround us.

You can visit the full collection & project website here.

To be honest, I was surprised by how much information about each object was available online. I was able to track down full histories of most objects, including information about the manufacturing company, the material, original newspaper advertisements, and other details I did not expect to find.

Winthrop pHisoHex bottle

Date: 1930-1950

Manufactured: New York, NY

Material: Low density polyethylene plastic

Description:

Winthrop-Stearns Inc. was a pharmaceutical company that underwent several mergers. A 1922 merger resulted in Sterling Drug, an American global pharmaceutical company that was later divided and sold to other pharma companies.

This particular bottle contained pHisoHex (pHisoderm with hexachlorophene), a preoperative cleansing agent for eye surgery. Initially used exclusively by surgeons, the product was later re-marketed to the public as a skin cleanser in the 1950s.

Polyethylene was first manufactured on a commercial scale during the Second World War by the British company Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and eventually American companies began to manufacture polyethylene in the U.S. After the war ended, polyethylene was used to create squeezable bottles for antiperspirant. The flexible squeeze bottle emerged in the 1950s as a high density form of polyethylene.

Here is the final presentation I shared with the class:

The feedback I received from the class was extremely helpful. Most notably, our instructor Stefani pointed out that this project invokes feelings of nostalgia, but perhaps not the disgust that we associate with trash. In short, by decontextualizing the objects we tend to forgot that all this stuff was trash when I found it. Another student suggested adding more objects that are identifiably “trash” – a take-away container, a bottle, a plastic bag, etc. I plan to make adjustments to the project as I prepare the project for ITP’s Spring 2016 show.